Your SQL Database Needs Test Data? Generate It Quickly With Python And Faker

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/photos/F8mx5zBVbyA?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText)](/assets/images/unsplash/kyle-sudu-F8mx5zBVbyA-unsplash.jpg)

For certain SQL use cases, you need a bunch of test data in your database. This test data can be generated with the help of Python, templates and the flexible Faker library.

All the code and generated test data files can be found in my GitHub repository https://github.com/mostsignificant/datagen.

The General Workflow

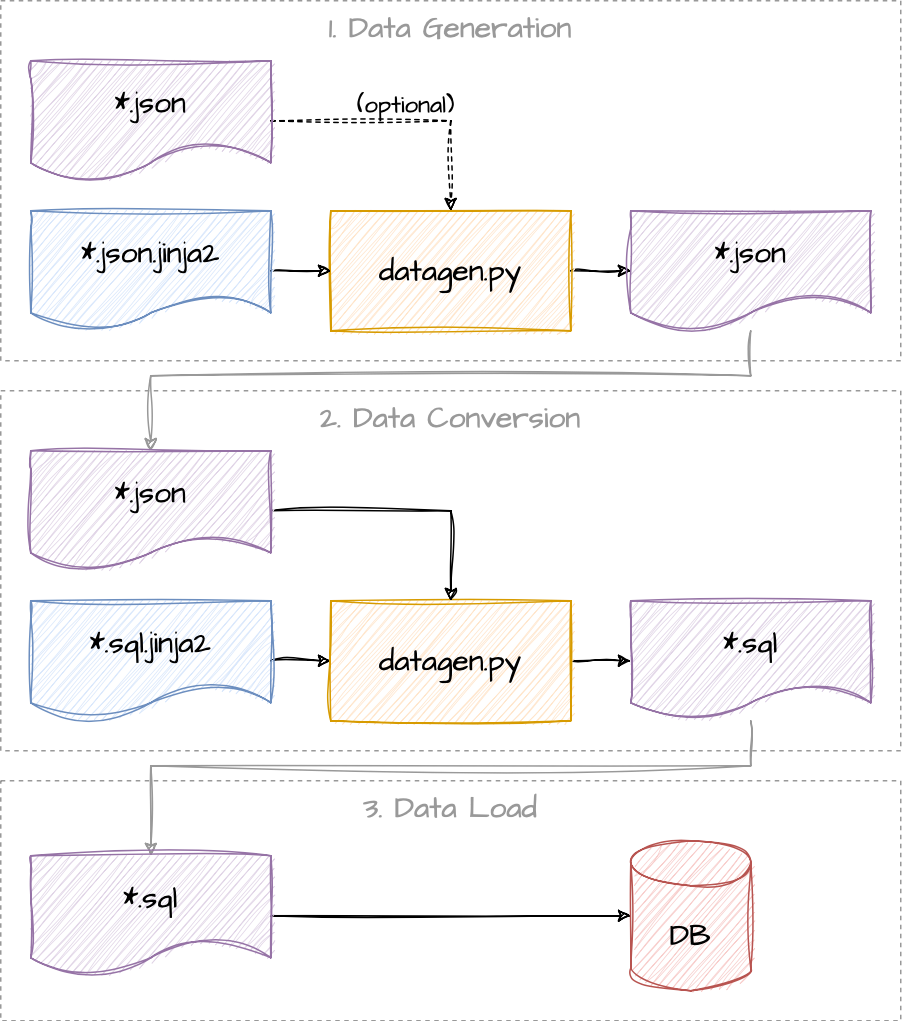

The idea behind the workflow is to use templates that can invoke the Faker library on rendering. The main component data generator stays flexible by receiving its input just from templates and optionally injectable JSON data. This way the data generator can also be used to just convert JSON data to any other format defined by the template file.

The workflow and its templates could be fitted to fill any other data storage (NoSQL, file store, a cranky tape drive, whatever). However I wanted to showcase in this example the JSON to SQL conversion capabilities of this approach (and search engines like keywords in the title).

The following figure depicts the planned workflow. It needs this two-step approach if data from previous steps needs to be used in the SQL scripts, for example for valid foreign keys. If you want to generate plain independent data you also directly generate the SQL scripts.

-

Data Generation

The first step takes an template to generate the test data in JSON format. Additional data from another, previously generated JSON file could be injected and used in the template rendering process, too.

-

Data Conversion

The generated test data in JSON files can then be converted to the target file format, in our case SQL scripts - more specifically simple

INSERTstatements. -

Data Load

The created SQL scripts will be executed against a database to load the data.

Why do we need the extra step with the JSON data? This extra step allows us to inject other JSON data into the generation step, for example for picking foreign keys. Additionally, you can use these JSON representations to later convert the data into any other format if needed.

Libraries Make Our Life Easier

The major part of this project is plugging together these two libraries:

-

Jinja2

The Jinja2 templating engine is used to render templates into files. Its ability to include loops allows us to generate arbitrary amounts of test data rows. Additionally we can inject callable objects into the template syntax, for example the Faker library.

-

Faker

The Faker library provides a load of methods for generating random numbers, addresses, names, email addresses, phone numbers, and much more. It also features localized providers if you need more localized names or addresses.

Faker is heavily inspired by PHP Faker, Perl Faker, and by Ruby Faker.

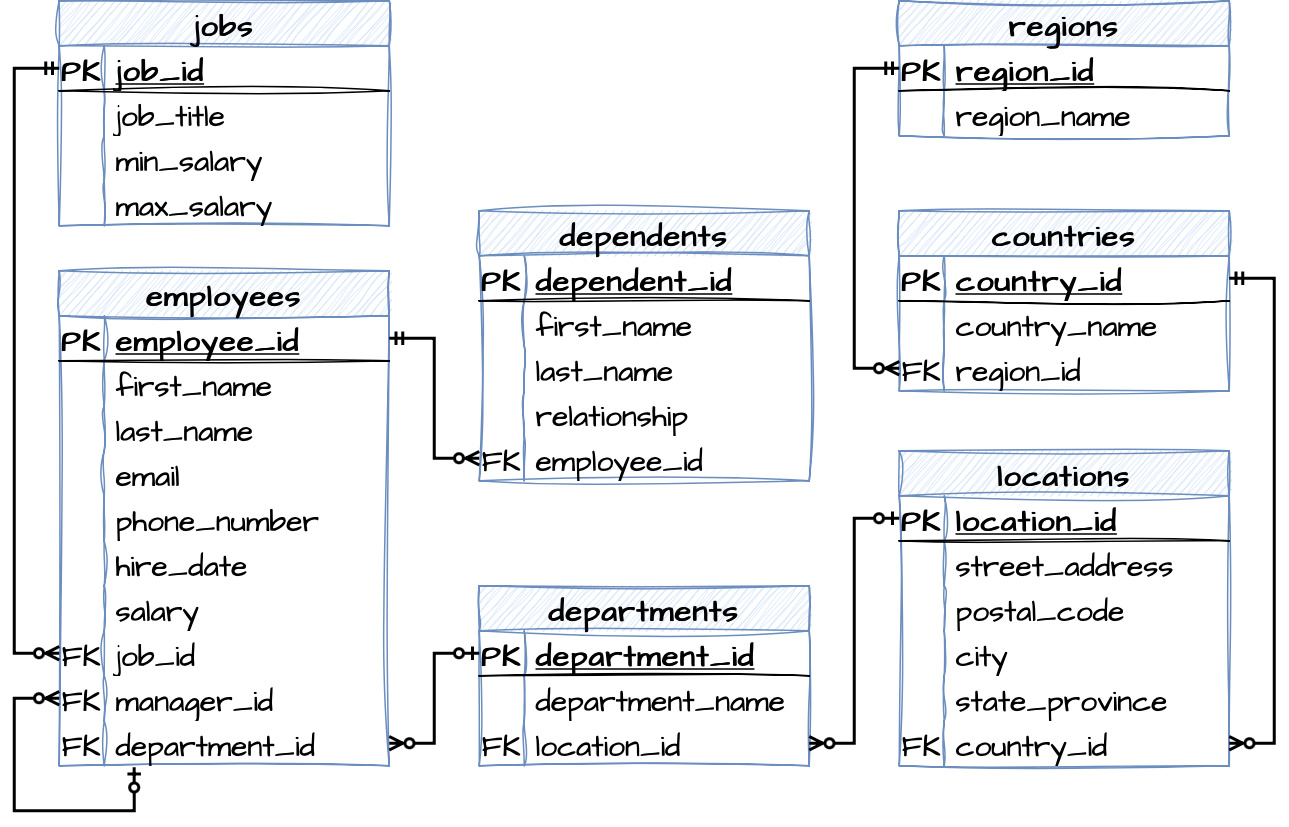

Data Model Required

We need a practice data model to generate our test data for. In this example we can use the HR data model from sqltutorial. It is a simple data model and the following figure depicts the seven tables and their relationships:

The example uses MariaDB as database. Therefore the repository contains the data model from the MySQL example and generates compliant code. The sqltutorial contains the code for other databases, too. Adapt the code and the template as needed.

Building The Data Generator

For our main use case we will be creating a Python script which generates the test data. We will call this script

datagen.pyand put it in our sample project’s root directory.

I like to start my scripts by defining the inputs in the form of accepted command line arguments:

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument('template', type=str)

parser.add_argument('--count', type=int, default=1)

parser.add_argument('--data', type=str)

parser.add_argument('--output', type=str)

args = parser.parse_args()

templateis the path to the template file to be usedcountis the number of test data rows to be generateddataare additional JSON files that can be injectedoutputis the optional name of the output file

Within the main() method we are preparing our Jinja2 environment and reading in the template directory - which we

just assumed from the passed command line argument.

def main(template: str, count: int, datafiles: str, output: str):

template_dir = os.path.dirname(template)

template_file = os.path.basename(template)

environment = Environment(loader=FileSystemLoader(template_dir))

The most important step is to pass an instance of the Faker object into the template engine environment. This

enables us to call all of its method from within a Jinja2 template.

environment.globals['fake'] = Faker()

Next we will read in an comma-separated array of JSON files. This way we can make the files’ data content available in the templates. Yes, this part could use a little bit more of input validation - but at the moment this milli-vanilli way of throwing the file content together is sufficient.

data = {}

if datafiles is not None:

for datafile in datafiles.split(','):

file = open(datafile)

data = data | json.load(file)

All that is left is template rendering and writing the result to a file - nothing new to be seen here. We are passing

the count parameter so it can be used to dictate the number of test data rows in the generated file. The

data parameter contains the JSON content we read in the step before.

template = environment.get_template(template_file)

content = template.render(count=count, data=data)

with open(output, mode='w', encoding='utf-8') as file:

file.write(content)

Magic Templates

The actual logic is within the templates. The following examples show some templates and tricks used to generate the test model.

First let us have a look at the template to generate regions. It uses the json method to generate the actual

JSON output. The count parameter determines the number of data rows. The attribute region_id is anything random

between one and 999999999. The region_name is a two-letter word picked from uppercase letters.

{

"regions": {{

fake.json(

data_columns=[

('region_id', 'random_int', {'min': 1, 'max': 999999999}),

('region_name', 'lexify', {'text': '??', 'letters': 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'})

], num_rows=count, indent=4)

}}

}

After calling the data generator, the JSON data looks similar to this:

{

"regions": [

{

"region_id": 14047538,

"region_name": "AH"

},

{

"region_id": 695946376,

"region_name": "HF"

}

]

}

For the case of countries, we are picking a random region_id from the injected data object (the regions we generated in the previous script). You will see the actual command line calls in the next chapter. Be careful with this template, since it could generate duplicate primary keys: the data model defines the country_id field’s data type as CHAR(2).

{

"countries": {{

fake.json(

data_columns=[

('country_id', 'lexify', {'text': '??', 'letters': 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'}),

('country_name', 'country'),

('region_id', 'random_element', {'elements': data['regions'] | map(attribute='region_id') | list })

], num_rows=count, indent=4)

}}

}

Interesting is the case of employees: the Faker library provides a lot of useful methods for the different fields’ data. You can find these methods in Faker’s person, address, and phone number providers.

Additionally this template uses the DTEncoder which is described in a later chapter about useful helpers. It will

serialize the data generated by the date_between() method: it picks a random date between today’s date and 30

years ago.

Similar to the countries template, we pick a random job_id, manager_id, and department_id from the supplied data that was generated earlier.

{

"employees": {{

fake.json(

data_columns=[

('employee_id', 'random_int', {'min': 1, 'max': 999999999}),

('first_name', 'first_name'),

('last_name', 'last_name'),

('email', 'email'),

('phone_number', 'phone_number'),

('hire_date', 'date_between'),

('job_id', 'random_element', { 'elements': data['jobs'] | map(attribute='job_id') | list }),

('salary', 'random_int', { 'min': 1000, 'max': 7500 }),

('manager_id', 'random_element', { 'elements': data['employees'] | map(attribute='employee_id') | list }),

('department_id', 'random_element', { 'elements': data['employees'] | map(attribute='department_id') | list }),

], num_rows=count, indent=4, cls=DTEncoder)

}}

}

This generates data similar to the following (for just one generated test data row). As you can see, the email value is not matching the first and last name of the employee. This could be irrelevant for test data. But if you need fitting company emails, you can have a look at the other Faker providers to get a company domain and concatenate this with first and last name in the template.

{

"employees": [

{

"employee_id": 299605329,

"first_name": "Ashley",

"last_name": "Williams",

"email": "barryhaynes@example.net",

"phone_number": "109.680.7478x954",

"hire_date": "2004-03-04",

"job_id": 358419952,

"salary": 2044,

"manager_id": 422380893,

"department_id": 898559056

}

]

}

The other templates are created accordingly. Their foreign keys have different dependencies to primary keys generated earlier. As your data model gets more complicated, the generation of test data could become potentially more complex.

There is an additional template needed to generate SQL scripts. This template is generic for any JSON input, so we do not need to create SQL templates for each test data set.

-- autogenerated test data

{%- set key = (data.keys() | list)[0] %}

INSERT INTO {{ key }} ({{ data[key][0].keys() | list | join(', ') }})

VALUES

{%- for object in data[key] %}

({{ object.values() | quotify | nullify | join(', ') }})

{%- if loop.index == data[key] | length -%}

;

{%- else -%}

,

{%- endif -%}

{%- endfor %}

This template takes the passed in data object and creates a single INSERT statement including all values. Closing

the values list is a simple if clause.

Running The Show

For generating data, we actually need to call the datagen.py script. The following command calls the data

generator for the regions template, generating five test data rows.

python datagen.py templates/regions.json.jinja2 --count 5

We will call the data generator again to generate countries. But this time, we are passing in the generated regions to use the generated region_ids to pick foreign keys.

python datagen.py templates/countries.json.jinja2 --count 15 --data regions.json

We repeat this accordingly until there are JSON files generated for each template. Be aware that you need to generate managers and employees separately if you want the employees to have an actual manager - you need the picked manager_ids as foreign keys.

After finishing this, it is finally time to generate SQL code. Convert the JSON files to SQL scripts via the following commands:

python datagen.py templates/insert.sql.jinja2 --data regions.json --output 001_insert_regions.sql

python datagen.py templates/insert.sql.jinja2 --data countries.json --output 002_insert_countries.sql

python datagen.py templates/insert.sql.jinja2 --data locations.json --output 003_insert_locations.sql

...

I have bundled the calls in its own tiny-shiny shell script - you should too if you do not want to go crazy or crazier than generally acceptable.

The Little Helpers

As always: not everything goes as smoothly as expected. Some helper classes and methods needs to be passed to the template engine’s environment to be available in the templates.

For converting dates into a string format, the Faker library’s json() method needs an adapted encoder for

serializing (and the isinstance() call only works if the datetime library is imported as import datetime

without aliasing, as answered

here):

class DTEncoder(json.JSONEncoder):

def default(self, obj):

if isinstance(obj, datetime.date):

return obj.strftime('%Y-%m-%d')

return json.JSONEncoder.default(self, obj)

We made the output command line parameter optional. This means we need a default mode if we do not have a name for

the output file. In this case, we are just using the name of the template file without the .jinja2 part.

if output is None:

output = template_file.replace('.jinja2', '')

We need two additional helper methods as Jinja2 template filters to handle quotes and the NULL value for any none objects in the JSON data.

def nullify(elements):

nullified = []

for element in elements:

if element is None:

nullified.append('NULL')

else:

nullified.append(element)

return nullified

def quotify(elements):

quotified = []

for element in elements:

if type(element) == str:

element = element.replace('\'', '\'\'')

quotified.append(f'\'{element}\'')

else:

quotified.append(element)

return quotified

Pass these methods as filters to the template engine’s environment.

environment.filters['nullify'] = nullify

environment.filters['quotify'] = quotify

Load The Data

Loading the data is just a few command line calls away. Since we are using MariaDB we can just use the mysql command line tool to load the generated SQL files:

mysql \

--host="mysql_server" \

--user="user_name" \

--database="database_name" \

--password="user_password" \

001_insert_regions.sql

Otherwise just command line into the database client and copy-paste the file content.

Bonus Steps

As always, there is room for improvement. The following ideas could help developing the data generation concept even further:

-

Input Validation The command line arguments and the read files are very fragile to invalid input, for example wrong JSON syntax. Implement more graceful error handling. Currently obscure exceptions could make the error search for the user a nightmare (or leave it in if you want to demotivate your users from touching your stuff and need job security).

-

Several templates at once Extend the command line arguments to accept several templates to bundle several calls into one.

-

Meta data in the generated file Make meta data in the template available, for example current date time or version of the data generator. This way you can backtrack the origin of a generated test data file.

-

Automate Data Loading Implement a generic mechanism to automatically load any generated files into the final data store, for example into a (No)SQL database.

-

Automatic generation of templates You could use some heuristics to automatically generate the templates from input like schema files, table definitions, or other sources. Match names of columns like first_name to the actual method in the Faker library. This is a more complex undertaking and needs a convention over configuration approach. However, the generated templates could still be manually curated to fit the final data model.

Keep on coding and keep on creating! I wish you all a successful 2023!