Create A Simple But Effective JSON File Converter With Jinja2 In Python

on [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/s/photos/long-exposure?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText)](/assets/images/unsplash/shiro-hatori-WR-ifjFy4CI-unsplash.jpg)

Photo by Shiro hatori on Unsplash

Need to convert a JSON file into another format? This can be realised quickly and reusable with a few lines of Python and Jinja2 templates. We will implement this with less than 30 LOC - and an example template to convert GeoJSON to KML and can be reused for many more conversions.

Converting files from one format into another is a task that appears more often than not in a software developer’s everyday life. Ask eight different software developers for their favorite way to do it and you get 128 answers. There are tools for out-of-the-box conversions, scripts, frameworks, libraries, but sometimes a simple solution is sufficient for the task at hand.

JSON is a popular format for semi-structured data. Use cases for converting JSON into other file formats are plenty: JSON to XML, JSON to another JSON dialect, etc. However, nobody wants to write a new parser and converter for each conversion from scratch. Today’s solution will be reusable for different use cases and might save time in the long run.

I have put the final Python script in a GitHub gist for reference.

Today’s Example: GeoJSON To KML

To demonstrate a quick and easy conversion, we are using an example from the Open Data world. The Austrian National Railway (ÖBB) provides files with their stations and routes on their Open Data portal. One of these files GIP_OEBB_STRECKEN.json is in the so-called GeoJSON format: an accessible format for encoding geographic data structures, based on JSON.

The following example shows a GeoJSON file. The file holds objects of type Feature. Several of those can be

bundled in a FeatureCollection. Each Feature has a geometry, which in itself holds coordinates.

These coordinates are an array of two or three numbers. These numbers are longitude and latitude (or easting and

northing), and optionally altitude (or elevation). You can read the full specification in the corresponding

RFC 7946.

{

"type" : "FeatureCollection",

"name" : "GIP_OEBB_STRECKEN",

"features" : [

{

"type" : "Feature",

"geometry" : {

"type" : "MultiLineString",

"coordinates" : [

[

[ 13.8282417878, 46.5874404328 ],

[ 13.8281239459, 46.5871572442 ],

// ...

]

]

},

"properties" : {

// ...

}

}

}

We want to implement a script that converts a GeoJSON file into a new file in Keyhole Markup Language (KML) format. KML is an XML notation for geographic data and annotations. KML files can be imported in viewers like Google Earth, which it was originally developed for. The format’s name stems from its history: Google Earth was formerly called Keyhole Earth Viewer, created by a company called Keyhole Inc., before being acquired by the big search engine behemoth.

The following example shows a simple KML file with its basic concepts:

- the standard XML declaration

- a

kmltag with its namespace reference - a

Documenttag for holding an arbitrary amount of Placemarktags, which enclose information about- annotation with

nameanddescriptionand - geography with

Pointtags and embeddedcoordinates

You can read more about it on the official Google Developers website.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<kml xmlns="http://www.opengis.net/kml/2.2">

<Document>

<Placemark>

<name>Vienna</name>

<description>Beautiful city in the east of Austria</description>

<Point>

<coordinates>16.363449,48.210033,190.0</coordinates>

</Point>

</Placemark>

</Document>

</kml>

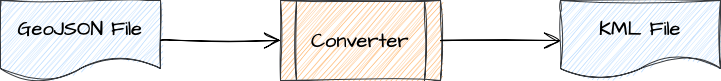

Regarding coordinates, we can already see a parallel to the GeoJSON format. Be aware, that the order of coordinates is longitude followed by latitude, as it corresponds to x- and y-axis, followed by elevation, mapping to z-axis. Converting from GeoJSON to KML is a mostly straight-forward process - with some exceptions as we will see later. The basic concept for this process is shown in the diagram below. This converter will enable us to show the ÖBB Open Data GeoJSON file with its stations and routes in Google Earth.

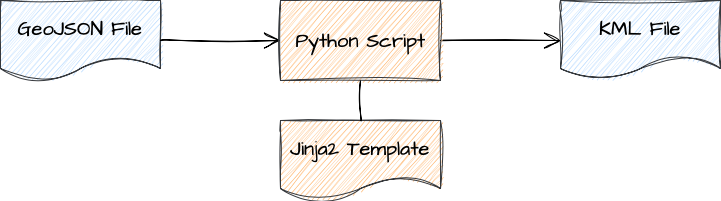

The Toolset

For today’s exercise, we will use a combination of two powerful tools from our inventory: Python and the Jinja2 template engine with its expressive syntax for templates. The Python script will ingest the source JSON file and convert it to any format as defined in an according template.

By using a template, we can decouple the converter from the actual conversion use case:

- If we need another type of target data format, we just write another template

- If we need an additional feature in the target file, we just change the template

Jinja2 is the template engine we need. It brings an expressive and powerful syntax with conditionals, loops, and much more. The following example from the official documentation shows some of its capabilities. For our converter, we will not use all of them - it is left to the reader’s creativity to extend the converter with additional features.

{% extends "layout.html" %}

{% block body %}

<ul>

{% for user in users %}

<li><a href="{{ user.url }}">{{ user.username }}</a></li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

{% endblock %}

There is an original version without version number just called Jinja for Python installations before version 3.

However, we need Jinja2 because we work with Python 3 (and you have my sympathy if you are stuck with anything

before it). You can simply install the templating engine via Python’s package manager pip:

pip install jinja2

The Script That Does The Job

Every script requires a super-funny and super-creative short name - but we are lacking both, so we are creating a file

called convo.py. At the top of the script, we add a descriptive one-liner and import the important packages:

import argparse # reading the command line parameters

import json # reading the input file

import os # file path magic

from jinja2 import Environment, FileSystemLoader # template magic

We write a main() function following the popular Python pattern,

even though the whole script will be short - but we will keep it concise for future enhancements. Within the

main() function we will parse three command line arguments:

inputis the JSON file to ingest and converttemplateis the applied Jinja2 templateoutputis the name of the final converted file

The intended syntax for calling the script from the command line should look something like this, for our example with the GeoJSON and final KML file:

python convo/convo.py \

GIP_OEBB_STRECKEN.json \

templates/geojson.kml \

oebb_strecken.kml

This call will cause the script to read the file GIP_OEBB_STRECKEN.json, use the template

templates/geojson.kml to convert the JSON data to final file oebb_strecken.kml. The following code lines

will set up the Python argument parser to ingest the three command

line arguments. The description of the parameters is left out to keep things brief, but is highly recommended to make

any script with command line arguments more useable.

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(

description='Converts json files to other formats via templates')

parser.add_argument('input')

parser.add_argument('template')

parser.add_argument('output')

args = parser.parse_args()

The next two lines take the input file and read out the JSON data into a Python dictionary object. The beauty of the dictionary is the fact that this data structure can later be directly passed into the template engine without any additional conversion code.

file = open(args.input)

data = json.load(file)

After parsing the JSON file, we load the template file. The second command line parameter called template is the

path to the actual template file. We construct an absolute path from it to get the directory name. The Jinja2

environment needs the directory with the template files and we will save some headaches by using absolute paths.

template_dir = os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(args.template))

environment = Environment(loader=FileSystemLoader(template_dir))

Similarly, we extract the template file name from the same command line argument. We will use the file name to load the template via the Jinja2 environment.

template_file = os.path.basename(args.template)

template = environment.get_template(template_file)

At the end, call the Jinja2 template to render the data. This render method takes a dictionary object, which is

the reason for this conversion code being so simple. The render()method returns an object of type string. This

string can be written to the output document.

content = template.render(data)

with open(args.output, mode='w', encoding='utf-8') as document:

document.write(content)

The Template That Does The Job

Additionally we need to write the according template. The following section shows the complete template for converting our GeoJSON file into a KML file. We use only basic Jinja2 features with conditionals and loops. These have to be enclosed in curly braces with the percentage sign. The minus sign at the opening tag tells the template engine to not replace this line by an empty line when rendering the output file.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<kml xmlns="http://www.opengis.net/kml/2.2">

<Document>

{%- if name %}

<name>{{ name }}</name>

{%- endif %}

<description>Converted KML file from GeoJSON</description>

{%- for feature in features %}

<Placemark>

{%- if feature.properties.GIP_OBID %}

<name>{{ feature.properties.GIP_OBID }}</name>

{%- endif %}

{%- if feature.properties.MAINNAME %}

<description>{{ feature.properties.MAINNAME }}</description>

{%- endif %}

{%- if feature.geometry.type == 'MultiLineString' %}

<LineString>

<coordinates>

{%- for coordinategroup in feature.geometry.coordinates %}

{%- for coordinate in coordinategroup %}

{{ coordinate.0 }},{{ coordinate.1 }}

{%- endfor %}

{%- endfor %}

</coordinates>

</LineString>

{%- endif %}

</Placemark>

{%- endfor %}

</Document>

</kml>

There are workarounds to fit the template to our specific input GeoJSON format:

- For the text of the

<name>tag inside the<Document>tag we are using the name of the whole GeoJSON file, which is not required in the GeoJSON standard. This means if the input file does not have a name in the JSON structure, the KML document will not have a name. - For the

<name>tag of the<Placemark>we are using one of the properties, which are not standardized. The same issue arises as with the previous workaround. - Similarly, for the

<description>tag of the<Placemark>we are using another one of the properties, causing the same issue again, if we have different input GeoJSON files.

To mitigate this, we could either use a different template for other GeoJSON input files or make the template more generic. For a more generic version, we could use the input or output file’s name as the KML document name. To do this, we have to include additional dictionary entries when passing the input file’s data to the template engine renderer. This exercise is left to the reader.

The Final Result

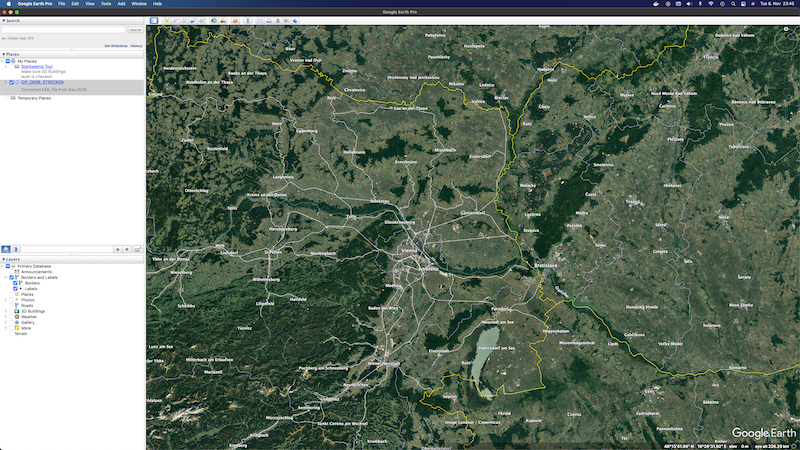

Finally, we can call the finished script with the ÖBB Open Data GeoJSON file and our template to convert it to KML:

python convo.py GIP_OEBB_STRECKEN.json templates/geojson.kml oebb_strecken.kml

The converted KML file can be imported in Google Earth Pro via File > Import … and selecting your KML file. The following screenshot shows the result on the map. The actual routes are drawn as white lines on the canvas.

Bonus Steps

For bonus points there are a lot of features that can be added to make our conversion script even more useful:

- More input file formats: support for formats like CSV, XML, or Parquet

- Convention over configuration: let’s make the template and output file name command line parameters optional and infer their names from the input file’s name

- Meta information for the templates: information like input/template/output file name, conversion timestamp, or Python version

Conclusion

This quick exercise showed the effectiveness of Python’s Jinja2 templates combined with its onboard JSON parser. It allows you to control the conversion logic in your templates and add additional output formats with new templates.

You can use this approach for your next file conversion task, but more importantly: keep on coding and keep on creating!